” Everything you see in a Fireworks display is chemistry in action ”

John Conkling , Chemistry Professor

It’s hard to imagine celebrating holidays specially new year without those fireworks. Because fireworks became a part of human life especially on time of occasions such as the New Year Celebration. A tradition that both fun and exciting those lights with different shape color and pattern at the night sky. As we grow older we still want to enjoy the dazzling magic of these aerial display to complete the joyous outdoor celebration.

Fireworks are a class of low explosive pyrotechnic devices used for aesthetic and entertainment purposes. They produce amazing bursts of colors that take a variety of shapes. It teach us some interesting chemistry, so let’s take a closer look at what they are and how they work

What’s inside a firework?

The source of most fireworks is a small tube called an aerial shell that contains explosive chemicals. All the lights, colors, and sounds of a firework come from these chemicals.

An aerial shell is made of gunpowder, which is a well-known explosive, and small globs of explosive materials called stars.The stars give fireworks

their color when they explode.

An exploding firework is essentially a number of chemical reactions happening simultaneously or in rapid sequence. When you add some heat, you provide enough activation energy (the energy that kick-starts a chemical reaction) to make solid chemical compounds packed inside the firework combust (burn) with oxygen in the air and convert themselves into other chemicals, releasing smoke and exhaust gases such as carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen in the process. For example, this is an example of one of the chemical reactions that might happen when the main gunpowder charge burns:

2KNO3 (potassium nitrate) + S (sulfur) + 3C (carbon in charcoal form) → K2S (potassium sulfide) + N2 (nitrogen gas) + 3CO2 (carbon dioxide).

Where do fireworks color come from?

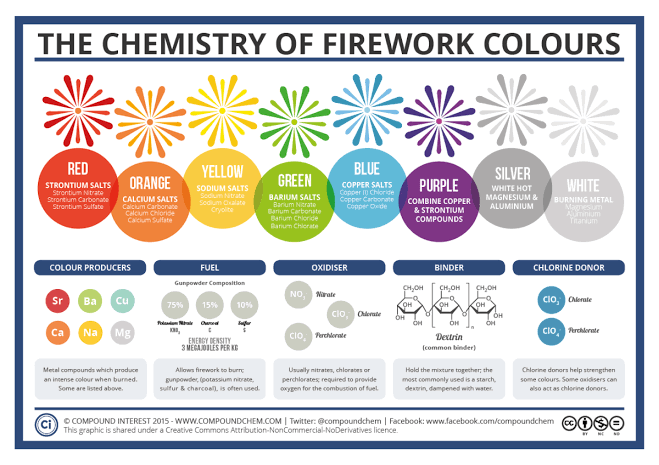

The colours in fireworks stem from a wide variety of metal compounds – particularly metal salts. ‘Salt’ as a word conjures up images of the normal table salt you probably use every day; whilst this is one type of salt (sodium chloride), in chemistry ‘salt’ refers to any compound that contains metal and non-metal atoms ionically bonded together. So, how do these compounds give the huge range of colours, and what else is needed to produce fireworks?

The most important component of a firework is, of course, the gunpowder, or ‘black powder’ as it is also known. It was discovered by chance by Chinese alchemists, who were in actuality more concerned with discovering the elixir of life than blowing things up; they found that a combination of honey, sulfur and saltpetre (potassium nitrate) would suddenly erupt into flame upon heating.

The combination of sulfur and potassium nitrate was later joined by charcoal in the place of honey – the sulfur and charcoal act as fuels in the reaction, whilst the potassium nitrate works as an oxidising agent. Modern black powder has a saltpetre to charcoal to sulfur weight ratio of 75:15:10; this ratio has remained unchanged since around 1781.

The combustion of black powder doesn’t take place as a single reaction and so the products can be rather complicated. The closest thing to a representative equation for the process is shown below, with charcoal referred to by its empirical formula:

6 KNO3 + C7H4O + 2 S → K2CO3 + K2SO4 + K2S + 4 CO2 + 2 CO + 2 H2O + 3 N2

Variation in pellet size of the gunpowder and the amount of moisture can be used to significantly increase the burning time for the purposes of pyrotechnics.

As well as gunpowder, fireworks will contain a ‘binder’ – used to hold the components together, and also to reduce the sensitivity to both shock and impact. Generally they will take the form of an organic compound, often dextrin, which can then act as a fuel after ignition. An oxidising agent is also necessary to produce the oxygen required to burn the mixture; these are usually nitrate, chlorates, or perchlorates.Different metals will have a different energy gap between their ground and excited states, leading to the emission of different colours. This is the exact same reason that different metals give different flame tests, allowing us to distinguish between them.

They’re hot!

Did you know that fireworks burn at greater than 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit? Keep your distance from fireworks to avoid a serious burn. Remember, after the firework has been lit, it’s still hot! Wait 20 minutes before discarding a firework.

Stay safe during the holiday!

© https://www.compoundchem.com/2013/12/30/the-chemistry-of-fireworks/

© https://www.explainthatstuff.com/howfireworkswork.html

ABOUT THE ARTICLE BLOG

This Science Article Blog is managed by the GROUP 3 BSC 2101 Criminology students in partial fulfillment in their course requirement as final project in General Chemistry.

DISCLAIMER

Any views or opinions expressed on this blog are accredited to the respective guest author and do not necessarily reflect to the University.